Introduction

Treatments used for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are under investigation for their efficacy to prevent RA in at risk groups. It is therefore important to understand treatment preferences of those at risk. We systematically reviewed quantitative preference studies of drugs to treat, or prevent RA, to inform the design of further studies and trials of RA prevention. Stated preference studies for RA treatment or prevention were identified through a search of five databases. Study characteristics and results were extracted, and the relative importance of different types of treatment attributes was compared across populations. Twenty three studies were included 20 of RA treatments (18 of patients; 2 of the general public) and 3 prevention studies with first-degree relatives (FDRs).

A benefit was more important than a risk attribute in half of the studies of RA treatment that included a benefit attribute and 2/3 studies of RA prevention. In studies with non-patient participants, attributes describing confidence in treatment effectiveness/safety were more important determinants of choice than in studies with patients. Given intense research focus on RA prevention, additional preference studies in this context are needed. Variation in treatment preferences across different populations is not well understood and direct comparisons are needed.

Methods

Research articles published in English between January 1957 and November 2021, describing studies that used quantitative preference elicitation techniques (e.g. conjoint analysis, discrete choice experiment (DCE)) to investigate preferences for RA treatment or prevention in adults aged 18 years or older were included. The following databases were searched to identify potential articles for inclusion: MEDLINE, PsycINFO; EMBASE, Econlit publications; and CINAHL. Search terms were developed by the authors and received expert input from a librarian at the University of Birmingham. Included articles were reviewed independently by two research assistants (GM and NW) using the 5-item Purpose, Respondents, Explanation, Findings, Significance (PREFS) checklist. The PREFS checklist was developed to access quality and validity across different types of treatment preference study. This checklist assesses whether

(1) preference assessment is clearly defined and is the main objective(s) of the study,

(2) there is the risk of a selection bias,

(3) enough methodological detail is available to enable replication of the study,

(4) there is a risk of bias arising from excluding data from the findings, and

(5) key results and significance tests were reported. Scores for each item and an aggregate score (ranging from 0 to 5) were calculated for each included study.

Data extraction from included articles was conducted by a minimum of two independent reviewers (JC, GS, research assistant). Extracted characteristics included the full reference of the source, study objective, stated preference methodology, and a description of attributes and levels and order of relative importance.

Results

Study selection results

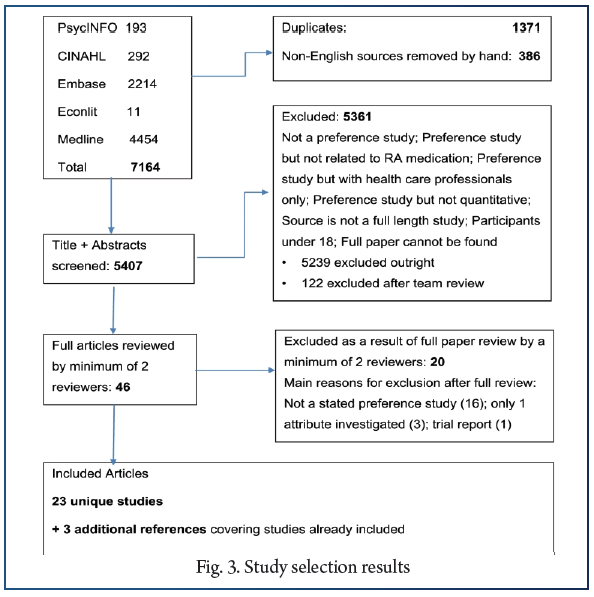

Twenty-three unique studies were included from the 5407 screened records (see Fig. 1). Three of these studies were described in multiple publications. Only one paper for each was included in the systematic review, with the others referenced. No studies were identified through the references of the included studies.

Twenty studies were of preferences for RA treatment and three studies for RA prevention. Study participants were patients with established (n = 17) or newly diagnosed (n = 1) RA; members of the general population (n = 2) who were asked to imagine they had RA; first degree relatives (FDRs) of patients with RA (n = 2); and one study included both FDRs and RA patients. Some articles also reported data from patients with other conditions, and healthcare professionals but these were not extracted for the current review. Sample sizes varied between 85 and 2663 individuals for the RA treatment studies and between 30 and 288 individuals in the prevention studies.

Results from the transparency

assessment with the PREFS checklist

Eight studies scored 3 (out of 5), twelve (including all three studies of treatments to prevent RA) scored 4, and three scored 5. Most studies failed to give information about how respondents differed from non-respondents reducing the score to 4 or less. Twenty sources provided either a sample task or a complete survey. Only the three studies of RA prevention, and two treatment studies (one with non-patient participants) included the background information provided to participants.

Attributes, attribute selection, and order

of relative importance

There was wide variation in the number and type of attributes included, and number of attribute levels across studies. Fourteen out of 20 studies of RA treatment preferences (12 of the patient studies and both general population studies) reported including at least one stakeholder in the form of RA patients in the attribute selection process. A benefit attribute was ranked higher than a risk attribute in both of the RA treatment studies with general public participants. However, for the studies with RA patients a benefit attribute was relatively more important than a risk attribute in only eight of the 16 studies that assessed a benefit attribute and for which a rank ordering for relative importance was available. Whereas a sample of African-American participants placed more relative importance on a risk attribute over benefits, the sample of white participants placed more relative importance on a benefit. A benefit was ranked higher than risk attributes in two of the three prevention studies. All but two studies included at least one treatment administration attribute.

Nine of the 18 RA treatment studies with patient participants also included cost as an attribute, whereas none of those with general public participants did, nor did the RA prevention studies. Two prevention studies reported excluding a cost attribute as it was ranked as the least important attribute in the qualitative research conducted to inform attribute selection. Moderate to large ranges of cost levels (e.g. ranging from 0 to $1000 per month or from ‘easy’ to ‘hard to afford’) were important determinants of choice (ranked first or second) in five of the nine studies. A number of attributes were coded as other including: physician experience or recommendation, the availability of nurse support, additional burden associated with the treatment in the form of regular medical tests or having to take it together with another medicine, and degree of uncertainty around benefit and risk estimates. Attributes that characterise the degree of certainty around the benefits or risk of treatment were included in two out of three prevention studies and one out of two RA treatment studies with general public participants.

Conclusion

Most stated preference studies relating to RA focus on the treatment of established disease. These find that treatment attributes, such as efficacy, safety, route/mode of administration and treatment cost are important determinants of choice. There are few studies that examine preferences of at-risk individuals for treatments to prevent RA. Given the increasing research focus on RA prediction and prevention, there is a need for further preference studies in this context to inform future management of RA and the design of prevention trials. Further research is also needed to assess the impact of variations in attribute presentation, predictors of preference heterogeneity and variation between populations, in the context of both disease treatment and prevention.

References:

1. Heidari B. Rheumatoid arthritis: early diagnosis and treatment outcomes. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2(1):161–70.

2. Miedany YE, Youssef S, Mehanna A, Gaafary ME. Development of a scoring system for assessment of outcome of early undifferentiated inflammatory synovitis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75(2):155–62.

3. Birch J, Bhattacharya S. Emerging trends in diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Prim Care. 2010;37(4):779–92.

4. Nikiphorou E, de Lusignan S, Mallen CD, Khavandi K, Bedarida G, Buckley CD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes in early rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Heart. 2020;106(20):1566–72.

5. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1580–8.

6. Durand C, Eldoma M, Marshall DA, Bansback N, Hazlewood GS. Patient preferences for disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.181165.

7. Gerlag D, Raza K, Lv B, al e. EULAR recommendations for terminology and research in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis: report from the Study Group for Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(5):638–41.

8. Mankia K, Siddle H, Di Matteo A, Alpízar-Rodríguez D, Kerry J, Kerschbaumer A, et al. A core set of risk factors in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR points to consider for conducting clinical trials and observational studies in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2021;7(3):e001768.

9. Mankia K, Siddle HJ, Kerschbaumer A, Alpizar Rodriguez D, Catrina AI, Cañete JD, et al. EULAR points to consider for conducting clinical trials and observational studies in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(10):1286–98.

10. Niemantsverdriet E, Dakkak YJ, Burgers LE, Bonte-Mineur F, Steup-Beekman GM, van der Kooij SM, et al. TREAT early arthralgia to reverse or limit impending exacerbation to rheumatoid arthritis (TREAT EARLIER): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial protocol. Trials. 2020;21(1):862.

11. van Boheemen L, ter Wee M, Turk S, van Beers M, Bos W, Marsman D, et al. The STAtins to Prevent Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAPRA) Trial: clinical results and subsequent qualitative study, a mixed method evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 2020;72.

12. Gerlag D, Safy M, Maijer K, et al. Effects of B-cell directed therapy on the preclinical stage of rheumatoid arthritis: the PRAIRI study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(2):179–85.