An overview of post-renal transplant anemia

Post transplant anemia (PTA) is not defined uniformly either in terms of timing after transplantation or in terms of the degree of anemia. However, most authors have suggested classifying PTA as: (1,2)

Early PTA: occurring up to 6 months after transplantation

Late PTA: occurring after 6 months of transplantation and may appear even up to 8 years later.

The prevalence of PTA at various time-points after transplantation is 20–51%. (1,2) PTA has been shown to be negatively associated with the following long term outcomes: increased rates of all-cause mortality, graft failure, congestive heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy and a decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). (1)

Iron deficiency is the major contributor towards early PTA. Inadequate iron stores at the time of transplantation, blood loss during surgery, increased iron utilization with the onset of erythropoiesis and poor nutrition all contribute to the occurrence of iron deficiency. (1)

Factors such as the female gender, lower eGFR levels and hypochromic red blood cells are said to be predictive of early PTA. Early PTA, in turn, is associated with late PTA. (1)

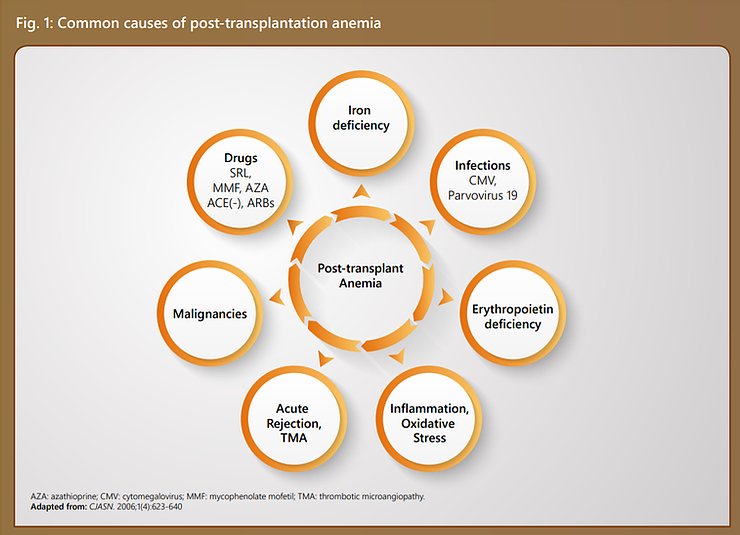

Apart from these, there are several other causes including drugs used in immunosuppression, post-transplant malignancies, oxidative stress, etc.

These factors have been illustrated in Figure 1.

Diagnosis of post-transplant anemia

The diagnostic evaluation of renal transplant recipients should include the following: (1)

An assessment for the usual causes of anemia as in the case of non-transplanted patients, including, red blood cell indices, reticulocyte counts, serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (transferrin), percent transferrin saturation, serum ferritin, folate and vitamin B12

Tests for the presence of hemolysis (haptoglobin) when clinically indicated (elevated reticulocyte counts, lactate dehydrogenase and indirect bilirubin)

Specific potential causes of anemia that may be unique to renal transplant recipients, such as the use of medications (immunosuppressive and antimicrobial), concurrent infections, etc.

Full anemia work-up approximately 3 months posttransplantation for early recognition and treatment to improve prognosis

Management of post-transplant anemia

Guidelines of the Renal Association, UK – 2017 (4)

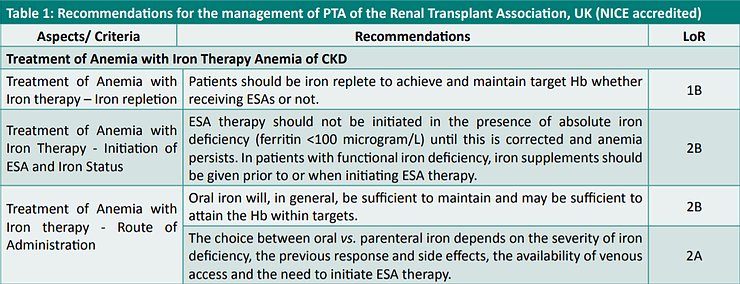

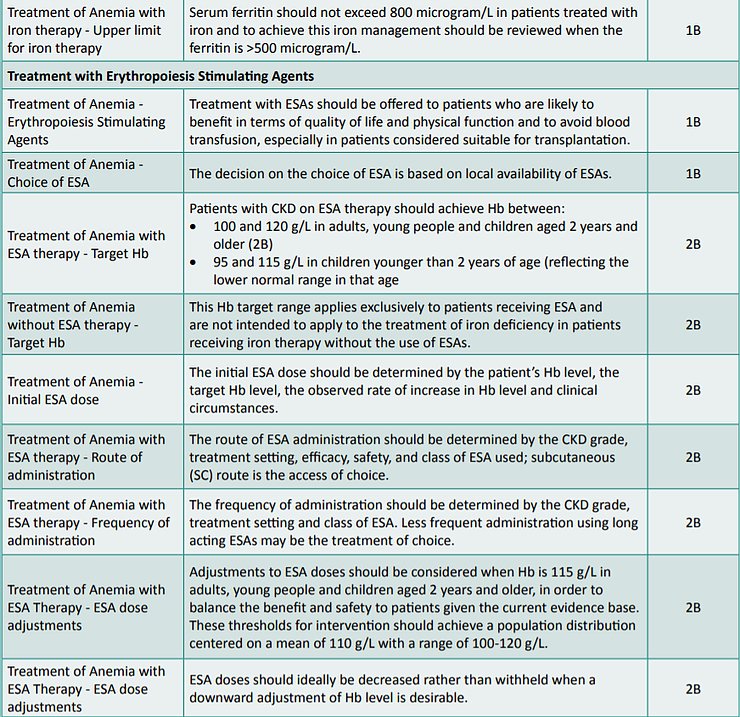

The Clinical Practice Guidelines on Anemia of Chronic Kidney Disease – 2017 promulgated by the Renal Association, UK and accredited by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), UK recommend that the treatment guidelines for anemia in renal transplant patients should be similar to those for CKD patients not on dialysis.

Accordingly, the recommendations made by these guidelines have been listed in Table 1.

Challenges associated with anemia confronting renal transplant patients

Enalapril-associated anemia

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) increases erythropoiesis by metabolizing N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyllysyl-proline which is a natural inhibitor of erythroid progenitors, (5) as depicted in Figure 2.

On this basis, it had been hypothesized that ACE-inhibition may cause anemia by increasing renal blood flow and consequently decreasing erythropoietin levels. (6)

Literature is replete with examples of post-transplant patients having developed enalapril-associated anemia.(6-8) Withdrawal of the drug results in cessation of its anemia-inducing effects. (6,8)

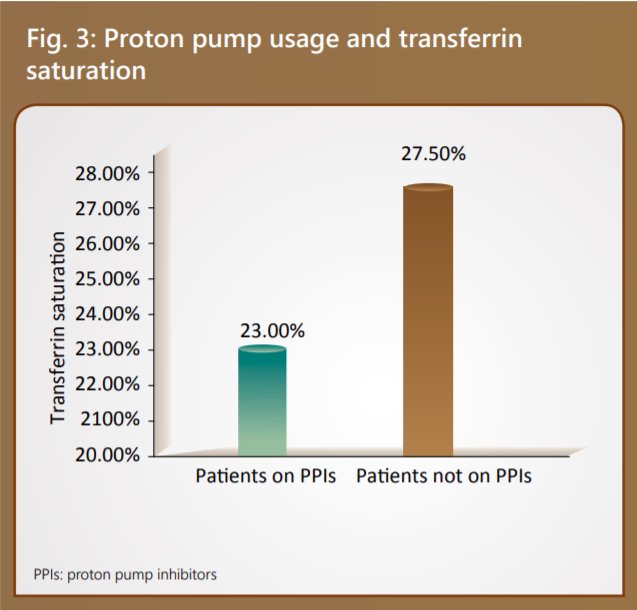

Proton pump usage and anemia

The use of proton pump inhibitors has been linked to poor iron absorption contributing to iron-deficiency. It has also been observed that patients on proton-pump inhibitors had a lower transferrin saturation, (9) as depicted in Figure 3. A strong association of iron depletion has been established in renal transplant recipients taking high doses of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (OR=1.57). Therefore, limiting the use of PPIs in renal transplant patients serves beneficial. (10)

Impact of immunosuppressive agents on erythropoeitin progenitor cells

Several immunosuppressant agents – including rituximab, thymoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS), calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (MTORi) like sirolimus, gancyclovir, valacyclovir and trimethoprim-sulphamethaxazole (TMP-SMZ) – are known to result in post-transplant anemia following renal transplantation. (11,12)

One of the most important causes of PTA due to immunosuppressive agents is the loss of renal allograft function, paralleling the loss of endogenous erythropoietin production in patients. (12) Steroid and CNI minimization/ withdrawal/ avoidance regimens (11,13) and optimization of immunosuppression (14) pave the way for better disease management in such circumstances.

Summary and Conclusions

Post-renal transplant anemia, is indeed, a major public health problem as a consequence of its high prevalence rates and its association with several deleterious consequences.

The diagnosis and management of PTA involves several complexities.

Guidelines recommend the use of ESAs and blood transfusion as means to overcome PTA.

However, the management of PTA is complex as it is confronted by several challenges posed by enalapril, proton pump inhibitors and various immunosuppressive agents. Optimization of treatment with appropriate drug modulation strategies remains the key to combat PTA.

References

1. Gafter-Gvili A, Gafterc U. Posttransplantation Anemia in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Acta Haematol. 2019; 142:37–43.

2. Schechter A, Gafter-Gvili A, Shepshelovich D, et al. Post renal transplant anemia: Severity, causes and their association with graft and patient survival. BMC Nephrology. 2019;20: Article number 51.

3. Mikhail A, Brown C, Williams JA, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline Anaemia of Chronic Kidney Disease. From the website of the Renal Foundation, UK. Available at: https://renal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anaemia-of-chronic-kidney-disease5d84a231181561659443ff000014d4d8.pdf;

Accessed on: Oct. 19, 2019.

4. Djamali A, Samaniego M, Muth B, et al. Medical Care of Kidney Transplant Recipients after the First Posttransplant Year. CJASN. 2006;1(4):623-640.

5. Rajasekar D, Dhanapriya J, Dineshkumar T, et al. Erythrocytosis in renal transplant recipients: A single-center experience. Indian J Transplant. 2018;12:182-6.

6. Graafland AD, Doorenbos CJ, van Saase JCLM. Enalapril-induced anemia in two kidney transplant recipients. Transplant International. 1992;5(1):51–53.

7. Sreeadhara CG, Narayanaswamy R, Lingaraju U, et al. Early initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in postrenal transplant period: A study from a state-run tertiary care center.

Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29(3):637-642.

8. Vlahakos DV, Canzanello VJ, Madaio MP, et al. Enalapril-associated anemia in renal transplant recipients treated for hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;17(2):199-205.

9. Lim AKH, Kansal A, Kanellis J. Factors associated with anaemia in kidney transplant recipients in the first year after transplantation: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:Article number: 252.

10. Douwes RM, Gomes-Neto AW, Eisenga MF, et al. Chronic Use of Proton-Pump Inhibitors and Iron Status in Renal Transplant Recipients. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1382.

11. Khalil MAM, Khalil MAU, Khan TFT, et al. Drug-Induced Hematological Cytopenia in Kidney Transplantation and the Challenges It Poses for Kidney Transplant Physicians. Journal of Transplantation. 2018;2018:Article ID 9429265.

12. Winkelmayer WC, Chandraker A. Pottransplantation Anemia: Management and Rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(S2):S49–S55.

13. Srinivas TR, Kriesche HUM. Minimizing Immunosuppression, an Alternative Approach to Reducing Side Effects: Objectives and Interim Result. CJASN. 2008;3(S2):S101-S116.

14. Boots JM, Christiaans MH, van Hooff JP. Effect of immunosuppressive agents on long-term survival of renal transplant recipients: focus on the cardiovascular risk. Drugs. 2004;64(18):2047-73.