Introduction

Inflammation plays a central role in determining transplant outcomes. Its intensity varies across living donation, DBD, DCD, and xenotransplantation, with pig xenografts provoking the strongest systemic inflammatory response. Inflammation activates macrophages, neutrophils, complement pathways, endothelial cells, and T-cells ultimately driving rejection and tissue damage through cytokine release and immune overactivation.

In their timely review, Ubaid et al. explain how inflammation arises from donor factors, recipient factors, and surgical processes in allotransplantation. In xenotransplantation, these are compounded by a broader systemic inflammatory response unique to cross-species transplantation. With rising global interest in kidney xenotransplants, the review provides a clear comparison of risks, mechanisms, and potential benefits across both transplant types.

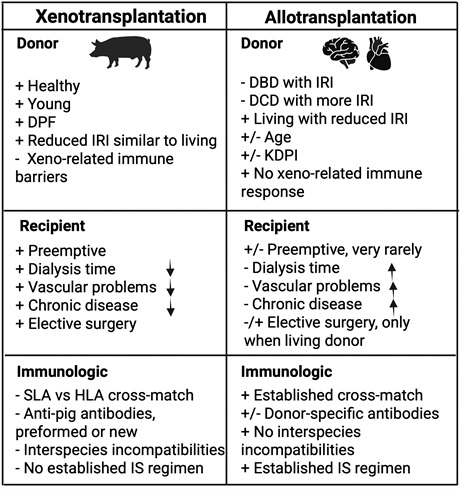

Figure 1. Benefit and pitfalls of xenotransplantation

Donor type strongly influences inflammation in allotransplantation—living donors have less ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI), while DBD and DCD donors show higher inflammation. In xenotransplantation, live donor pigs reduce donor-related inflammation and allow planned elective surgery, similar to living donor transplants. Although genetic modifications and pathogen-free pig facilities lower infection-related inflammation, long transport distances still increase cold ischemia time and IRI, which machine perfusion can reduce but not eliminate.

Recipient factors are similar in both transplant types, but xenotransplantation offers the advantage of earlier intervention before chronic kidney disease or long-term dialysis cause systemic inflammation. Studies show worsening kidney function correlates with elevated inflammatory markers like IL-6, CRP, and TNF-α. Even with ideal conditions, xenotransplants still trigger a systemic inflammatory response due to species incompatibilities involving immunity and coagulation.

Surgically, allografts and xenografts undergo similar implantation procedures, so donor and recipient quality mainly determine inflammatory outcomes. Robotic surgery may help reduce inflammation in allotransplantation, but it is not yet used in xenotransplantation, though may become feasible as experience grows.

Other important immunological factors contributing to inflammation in allotransplantation versus xenotransplantation include the following:

- Crossmatch testing, which is routine in allotransplantation but remains a challenge in xenotransplantation.

- The role of donor-specific antibodies in allotransplantation versus anti-pig antibodies in xenotransplantation, depending on specific genetic modifications.

- Differences in matching between HLA and swine leukocyte antigen (SLA).

- Interspecies incompatibilities between signals and ligands (eg, signal regulatory protein alpha-CD47 mismatch, species-specific major histocompatibility complex differences, and Natural Killer Group 2, member D–porcine UL16 binding protein 1 interactions in natural killer cells7).

Conclusion

Advances in genetic engineering and better understanding of swine leukocyte antigens (SLA) may allow creation of class I or II SLA-knockout pigs, helping overcome major histocompatibility differences and reducing anti-pig antibody responses. Future donor pigs may even express selected HLA molecules, enabling more personalized xenografts.

A deeper understanding of inflammation is essential for improving transplant survival. Progress in targeted anti-inflammatory therapies, genetically engineered pigs that reduce inflammatory triggers (e.g., human heme oxygenase-1 expression), and choosing the most suitable graft—whether allograft or xenograft—will continue to improve outcomes. With xenografts entering clinical practice, a new and promising era in transplantation is emerging, despite ongoing challenges.

References

1. Ubaid F, Ezzelarab MB, Cooper DKC. The relative roles of inflammation in kidney allo- and xeno-transplantation. Transplantation. 2026;110:e80–e89.

2. Meier RPH, Pierson RN 3rd, Fishman JA, et al. International Xenotransplantation Association (IXA) position paper on kidney xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2025;109:1313–1328.

3. Lee WK, Lee HC, Lee S, et al. The influence of specific pathogen-free and conventional environments on the hematological parameters of pigs bred for xenotransplantation. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1132.

4. Gupta J, Mitra N, Kanetsky PA, et al. CRIC Study Investigators. Association between albuminuria, kidney function, inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1938–1946.

5. Iwase H, Ekser B, Zhou H, et al. Further evidence for sustained systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients (SIXR). Xenotransplant. 2015;22:399–405.

6. Ezzelarab MB, Ekser B, Azimzadeh A, et al. Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients precedes activation of coagulation. Xenotransplant. 2015;22:32–47.

7. Lopez KJ, Spence JP, Li W, et al. Porcine UL-16 binding protein 1 is not a functional ligand for human natural killer cell activating receptor NKG2D. Cells. 2023;12:2587.

8. Estrada JL, Reyes LM Wang ZY, et al. Generation of SLA-DQ knockout pigs and screening for anti-SLA-DQ antibodies in sera from naïve and HLA Class II-sensitized patients. Transplantation. 2025;109:1357–1366.

9. Li P, Walsh JR, Lopez K, et al. Genetic engineering of porcine endothelial cell lines for evaluation of human-to-pig xenoreactive immune responses. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13131.